How does the shoulder work?

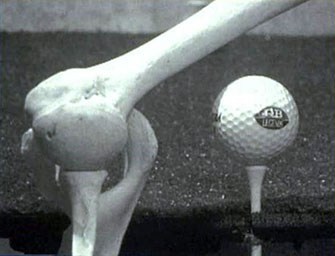

The shoulder, like the hip, is a ball and socket joint. Unlike the hip however, the socket is very shallow and is not stable enough to hold the head of the humerus in place. It is more like a golf ball on a golf tee.

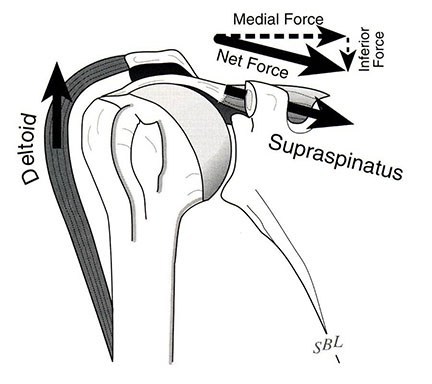

This gives the joint a large range of motion but as a consequence it also means that it is potentially unstable. To function normally, muscles on both sides of the joint must work together to hold the joint in place during movement. This means that when the deltoid muscle lifts the arm out from the side of the body, the supraspinatus and other muscles of the rotator cuff work to keep the head of the humerus (the ball) located in the center of the glenoid (the socket). Without the stabilizing force of a properly functioning rotator cuff shoulder motion is compromised.

In the normal shoulder this mechanism is so finely tuned that it always keeps the reaction force of the humerus at right angles to the joint. This allows the large muscles of the upper extremity such as the deltoid, pectoralis major or latissimus dorsi to do the heavy lifting while the smaller muscles work to keep the shoulder joint motion stable and pain free.

Figure 1: Note the similarity between the shoulder and the golf ball and tee.

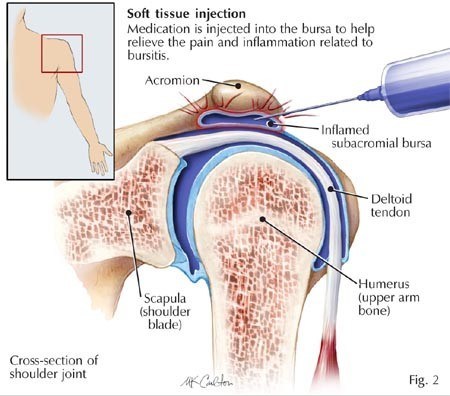

Figure 2: The large Deltoid pulls upwards while the Supraspinatus keeps the ball on the tee.

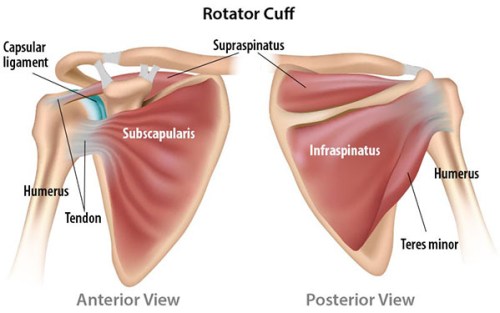

The Rotator Cuff

The rotator cuff is made up of 4 muscles which originate from the shoulder blade (scapula). The tendons of the muscles converge into a single flat sheet, wrapping around the humeral head (golf ball). Infraspinatus and teres minor are at the back, supraspinatus is on top and subscapularis is at the front. Supraspinatus is by far the most commonly torn tendon.

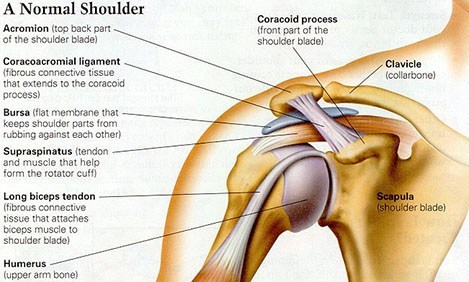

The tendons fill a very narrow space, with the humeral head below and the acromion (bony roof of the shoulder) above.

What is impingement syndrome/bursitis?

With overuse or traumatic injury the shoulder can become painful because it becomes inflamed in the space between the rotator cuff and the acromion (bony roof). This space contains a bursa which is a small sac that helps with motion and lubrication between tissues. The bursa can become inflamed and painful with friction occurring between the acromion and cuff tissues. This is called impingement syndrome or subacromial bursitis.

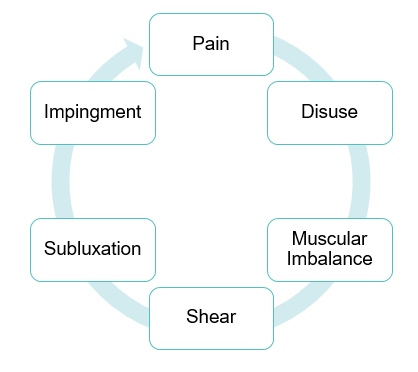

The pain causes the patient to stop moving the shoulder normally which in turn causes weakness and dysfunction of the rotator cuff and stabilizing muscles of the shoulder blade. As a result of the dysfunction, the motion of the shoulder becomes more abnormal, causing further abutment of the soft tissues of the shoulder against the acromion because of a failure of the muscles to control the motion of the shoulder. The cycle of impingement and inflammation can continue until the pain and motor dysfunction are addressed.

Figure 3: The vicious cycle of impingement and loss of function

Why do the cuff tendons tear?

There are a number of reasons. Like the rest of our body, the cuff tendons lose strength and flexibility as we age. Cuff tears before the age of 40 years are rare.

Age: The risk of rotator cuff tear, symptomatic or asymptomatic dramatically rises with each decade. The likelihood of a rotator cuff tear rises from near 0% before the age of 40 to 10% in the 50s, 15% in the 60s, 26% in the 70s and 37% in the 80s!

Overuse/Impingement: Workers who frequently need to use the arm overhead, such as construction workers, can eventually suffer structural failure of their cuff tendons due to wear and tear which is often preceded by recurrent bursitis or impingement.

Trauma: A heavy fall, a traction injury (trying to catch your fall with a trip down stairs), a twisting injury, a throwing injury or a heavy lifting injury can all result in a cuff tear.

Diagnosis

Pain is often felt part way down the arm but can radiate all the way to the elbow and into the trapezius. After an injury some patients find it hard to lift the arm at all for a few days. The pain can be severe and often feels worse in bed at night. It is difficult to sleep on the injured side. Lifting and reaching up or out can feel weak and painful.

Examination often reveals weakness in certain movements. Xrays often look normal but are necessary as there is a great deal of information gleaned from this simple and inexpensive test. An ultrasound scan can show the tear and an MRI can be very useful in further delineating the damage to the shoulder. An MRI can show the surgeon other injuries that may be present and also demonstrate how old the tear is and how likely it is that the tear will be successfully repaired.

If the ultrasound provides enough information we may not need to order an MRI, but in certain cases it is required to obtain that added information.

What is the difference between a partial tear and a full thickness tear?

A partial tear is a tear within the fibers of the rotator cuff tendons. This may be on one side of the tendon, either on the joint side (bottom side) or the subacromial space side (top side) of the tendon. Alternatively this may be within the fibers and not visible if looking directly at the tendon.

It is uncommon that these tears need to be treated surgically as they can be treated very successfully with non-operative modalities.

A full thickness tear is one that leaves a hole in the tendon and allows for a connection between the subacromial space and the joint. These tears can be complete or incomplete, which means that the tendon is either completely or incompletely detached with the tear that is present.

Will my cuff tear heal without surgery?

Rotator cuff tears do not heal on their own. Partial tears, small full thickness tears and some large full thickness tears can be treated with anti-inflammatory medication and a focused strengthening program which can allow them to become completely asymptomatic or pain free.

Will my tear get bigger?

Tears can get larger over months and years making repair more difficult or impossible in some cases. There is no specific predictor for tear size increase. Trauma can definitely increase it, but it may just be time. It is thought that about 50% of tears increase with time. An increase in size is usually indicated by a return of pain and other symptoms. Which can act as an indicator to pursue further treatment such as surgery.

Treatment

The first option is non-operative. Anti-inflammatory pills and Tylenol can help settle the pain and improve function. Physiotherapy is very helpful to rebalance the rest of the shoulder muscles and can often lead to a good return to function. The first step is to ensure that the shoulder has a full range of motion. Once this has been achieved, the cuff muscles will respond to a strengthening program.

A cortisone shot is often very helpful to allow patients to get pain under control and thus improve strength and motion. This will result in a significant improvement in 75% of patients over 6-12 weeks.

Cortisone is a steroid that is injected into the subacromial space, (the area between the acromion and the rotator cuff). The goal is to decrease the inflammation within this space and thus decrease impingement and pain. This usually allows further progress with physiotherapy.

There is a tiny risk of infection with an injection and very few other side effects. It is commonly more painful for 1-2 days and then settles. A week after the injection, physiotherapy is started to try to ensure a long term response. Without a guided strengthening program to rebalance the shoulder, the pain will return after the cortisone wears off.

There is no lifetime limit to the amount of injections, but we try to limit the number to a specific location. Repeat injections will depend on your response to the initial injection and duration of benefit. One to two injections into this space are safe.

Non operative treatment is successful in a large number of patients. Physiotherapy and medication to control inflammation should be started on all patients after the diagnosis of rotator cuff impingement or tear.

Large full-thickness tears in physiologically young patients are more likely to fail conservative management. In patients, especially those under 50, with a traumatic tear surgery is usually warranted. Patients with physical jobs or recreational activities are also more likely to decide on surgical intervention. These options for treatment can be discussed with your MOCSM physician during your consultation.

Cortisone Injection

Shoulder Rotator Cuff Repair